In my last article, I looked at the giant corporations of the malting world. Now I’ll examine the mid-sized malting companies that supply today’s craft and home brewers, focusing on their local sourcing and global reach.

Background

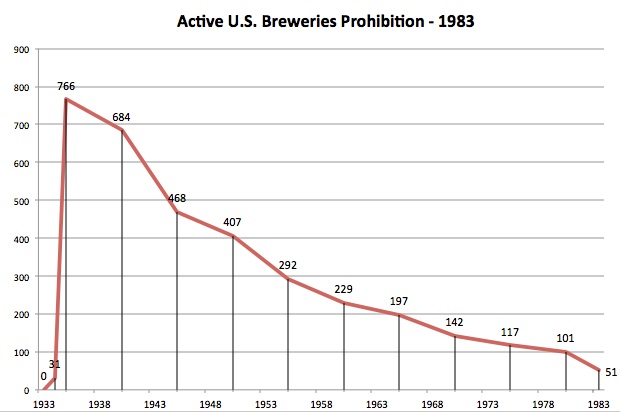

Between the repeal of prohibition and the 1980’s, the American brewing industry experienced a period of tremendous consolidation and homogenization. By the mid 80’s, an industry that a century earlier had been regional and diverse had shrunk to only a few companies, with global reach but limited variety and questionable quality. In 1983 – the low point of American brewing – the largest five American brewing companies controlled 92% of all beer production in the country. Those top five were Anheuser-Busch (Now AB-Inbev), Miller and Coors (now MIiller-Coors), Pabst and Stroh (both now owned by Pabst, which was just last week sold to the Russian company Oasis), and Heileman (now City Brewing Company, makers of Sam Adams). So the five largest beer companies from 1983 are now four much larger companies.

These brewing companies (I’ll refer to them as “BMC” from now on, short for “Bud-Miller-Coors”) all primarily make very pale lagers with high percentages of adjuncts in their recipes. For non-brewers in the crowd, an adjunct is a source of sugar that is not raw or malted grain. Typically rice solids or corn sugar, an adjunct boosts alcohol strength without adding much body or flavor. Rice and corn also have the favorable quality of being very cheap, so BMC use a lot of these ingredients: Budweiser is made with 30% rice; Coors uses 30% corn; Miller Light uses an unspecified amount of high fructose corn syrup.

Adjuncts only provide sugar, though; they don’t supply other organic chemicals that are needed for beer production, including diastatic enzymes (alpha and beta amylase, which convert starch to sugar to provide food for the yeast) protein (necessary for clarity and head retention), and nitrogen (Free Amino Nitrogen, or FAN, needed for yeast health). Barley malt has these nutrients in plentiful amounts; a barley-only or “all malt” beer naturally has enough of each chemical for healthy beer production. Beers with a high percentage of adjuncts need to get these substances from somewhere else.

The two-row barley long used in most European beers has just enough of these nutrients for an all-malt beer. On the other hand, six-row barley has significantly more enzymes and protein, enough to compensate for the lack of them in adjuncts. So brewers of beers with a high amount of adjuncts prefer six-row barley. As with most other crops, breeding programs have been used to change barley for malting, increasing the favorable characteristics and decreasing unwanted traits. As the brewing industry consolidated and increasingly focused on brewing adjunct lagers, the malting industry followed along with the demand, producing barley with more protein, enzymes, and FAN, (allowing for the use of higher amounts of cheap adjuncts) and decreasing the negative characteristics (namely flavor, which in six-row barley can be rather course). More chemistry, less taste, cheaper beer, higher profits. Which is how you end up with a crazy stat like this: in 2012, despite the rise of craft brewing, U.S brewers made 12% of the world’s beer using only 7% of the world’s malt. The missing 5% is basically corn and rice sugar, cheap, fermentable, and tasteless.

The two-row barley long used in most European beers has just enough of these nutrients for an all-malt beer. On the other hand, six-row barley has significantly more enzymes and protein, enough to compensate for the lack of them in adjuncts. So brewers of beers with a high amount of adjuncts prefer six-row barley. As with most other crops, breeding programs have been used to change barley for malting, increasing the favorable characteristics and decreasing unwanted traits. As the brewing industry consolidated and increasingly focused on brewing adjunct lagers, the malting industry followed along with the demand, producing barley with more protein, enzymes, and FAN, (allowing for the use of higher amounts of cheap adjuncts) and decreasing the negative characteristics (namely flavor, which in six-row barley can be rather course). More chemistry, less taste, cheaper beer, higher profits. Which is how you end up with a crazy stat like this: in 2012, despite the rise of craft brewing, U.S brewers made 12% of the world’s beer using only 7% of the world’s malt. The missing 5% is basically corn and rice sugar, cheap, fermentable, and tasteless.

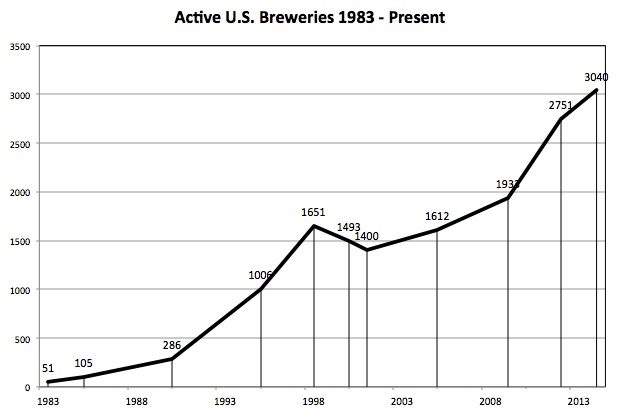

About that craft brewing industry: here’s a short history for the uninitiated. Very few local breweries survived into the early 70’s, among them Anchor in San Francisco and Ballantine in Newark (now defunct, its recipe lost, but recently re-created by Pabst, with help from homebrew clones). In the late 1970’s, a few microbreweries opened (New Albion in 1977; Sierra Nevada and Boulder in 1979). Homebrewing was legalized in 1978. More local breweries and brewpubs opened as the first generation of legal homebrewers went professional. After a brief correction in the late 90’s, the craft brewing movement took off in earnest. First dismissed as a fad, and then marginalized as a niche movement, the craft brewing industry has experienced three decades of double-digit growth, and now comprises 8% of all beer volume in the U.S.

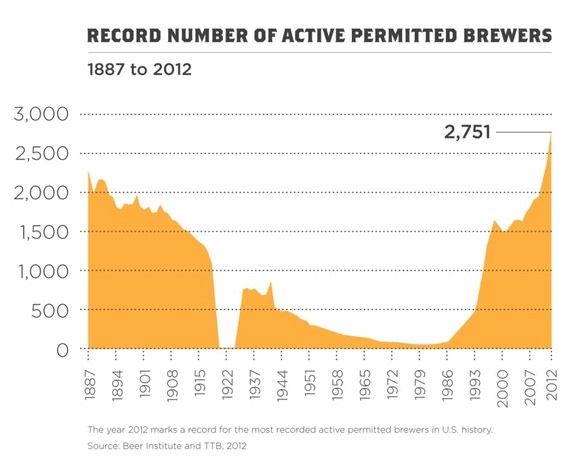

The overall historical picture looks like this; 2012 is the magic year when the number of post-prohibition breweries surpasses the maximum number pre-prohibition:

A number of factors have contributed to the rapid growth since 1990: the spread of the foodie movement east from the Pacific coast; the reduced cost of international travel (allowing more Americans to experience non-shitty British, Belgian, and German beer for themselves); subsequent waves of homebrewers becoming pro brewers; the anti-globalism protests of the late 1990’s; the anti-corporatism protests of the 2000’s; and the rise of the internet and social media (allowing small brewers to compete for local customers in a global marketplace).

An item that belongs at the top of this list: the growth of mid-size malting companies. We take for granted now that small brewers (and homebrewers) can easily get their hands on quality malt. But the 1980’s must have been a scary time to own a microbrewery; getting malt and hops in reliable quantity and quality would have been the single biggest challenge facing small brewers. After all, what good does it do to work and work to create a demand for quality beer when you can’t assure the supply? The fact was that the large malting companies had supply contracts with the large brewing companies that spanned decades; microbreweries of the 80’s and 90’s were forced to purchase their supply from the leftover scraps.

A bit of an aside is due here. The homebrewers of that era are the patron saints of today’s craft beer world, and being a homebrewer in the 80’s must have been no picnic. Those guys and girls struggled to find reasonably fresh malt extract to brew with; the reliable supply of floor-malted two row English barley that I take for granted (as cheap as a dollar per pound, who knew) was only a distant pipe dream. Cheers, pioneers!

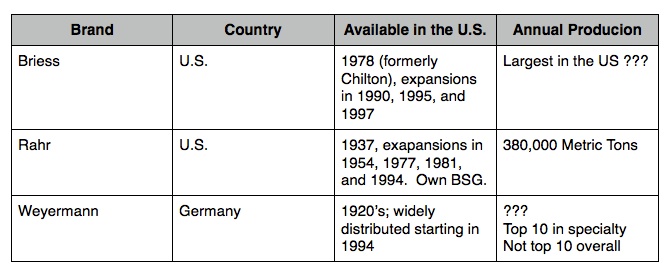

Take a look at this list of the companies that supply the bulk of the malt to today’s craft and home brewers, and when they started supplying the U.S. market:

1994-1995 seem to be magic years; Briess underwent a major expansion, and Rahr formed Brewer Supply Group (now known as BSG) which distributes, among others, Briess and Weyermann. Also of note is the fact that two of the three biggest suppliers are U.S.-based, conducting the majority of their malting operations and sales domestically.

For maltsters, the last 30 years have been a Field of Dreams tale: Demand from small brewers helps stabilize supply, which gives more brewers the supply confidence to go pro, which increases demand. All of which helps homebrewers achieve a quality supply line, too, as we simply piggyback on the craft brewers.

Current State of Mid-Sized Maltsters

In March of this year, the Brewer’s Association release a white paper, titled Malting Barley Characteristics for Craft Brewers. This paper is the summation of a 36-month study by the BA into the current state of the malt supply chain for craft brewers. The paper “identified malt supply mismatch as a potential impediment” to the growth of craft beer brands, and pointed out a number of “gaps” between the needs of craft brewers and the existing malt supply chain. Notable gaps include malts with too much protein and enzyme content, and not nearly enough flavor.

In other words, much of today’s malt meets the needs of brewers who use lots of adjuncts, but it is not particularly suitable for use by craft brewers, who tend to brew all-malt beers. The malting industry spent the better part of century adapting to meet the needs of adjunct brewers, resulting in these supply gaps. Craft brewers need maltsters to change course. And the demand will be there for malt companies to do so, or so says the Brewer’s Association forecast.

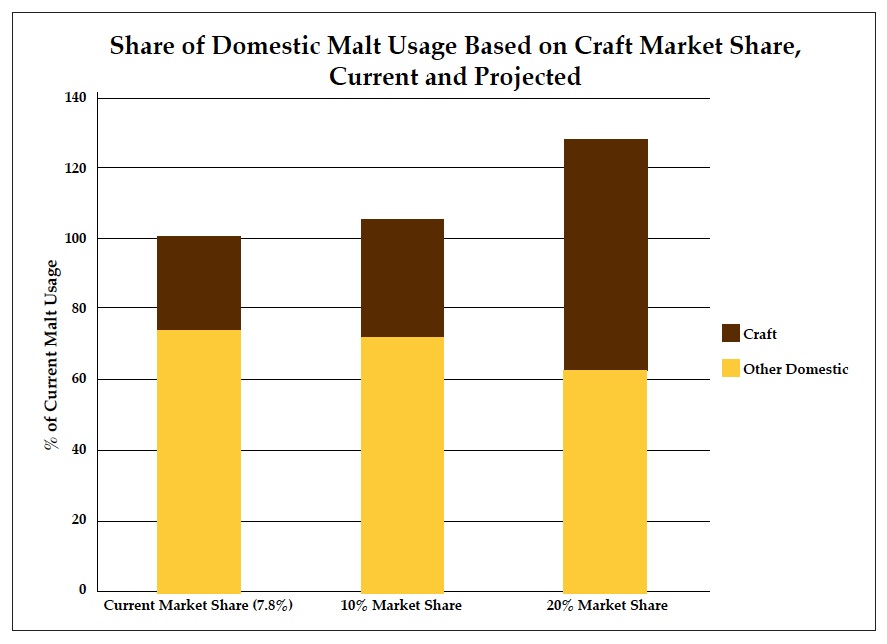

Crazy stuff, this: if trends continue, in a few short years, craft brewers will make 10% of the beer in this country, using more than 25% of the malt. Which is more than the malt industry is currently able to supply. Brewers need maltsters to grow, quickly, in a very targeted way.

Prospects for growth

Will the overall trends toward homogonization and globalization of the worldwide malt supply chain continue, or will it reverse course, becoming more responsive to the needs of the craft brewing industry? What are the future prospects of the malting companies that currently supply the craft brewing industry?

Researching these mid-size malting companies is much more difficult than finding information about the larger ones, because the Briess’s and Weyermann’s of the world are privately owned companies, rather than international corporations with quarterly reports and shareholders’ statements. For example, I still haven’t been able to find out the annual malt production of Briess, arguably the biggest supplier of malt to the American craft brewing industry.

That said, representatives of a few of these mid-size companies were kind enough to respond to my requests for information about their international marketing and sales. A Briess spokesman indicated that they sell the majority (> 90%) of their malt in the United States. One caveat: Briess sells about half of their brewer’s malt through their distribution chain (of which Weyermann’s BSG is one link). Briess’s distributers sell more Briess malt overseas than Briess actually does. It was also pointed out that both Briess and its distributors sell malt to food companies apart from brewers (this undoubtedly also applies to all other malting companies). The complexity of their distribution chain makes numbers like international vs. domestic sales to brewers very difficult to track.

A representative from the German maltster Weyermann expressed similar sentiments about both the complexity of their distribution chain (BSG in the United States, Gilbertson & Page in Canada), and the diversity of the products their malt ends up in. In general terms, though, Weyermann exports over half of the malt they produce, to 135 countries on six continents. The United States is their largest export market. Weyermann claims to have been the first company in the world to focus on producing the wide varieties of malt that are required by the U.S. craft brewing industry, and their diverse product catalog certainly supports that assertion. They also claim to have been the first non-American malting company to recognize and focus on supplying U.S. craft brewers; again, this is a tough statement to dispute.

Weyermann has experienced decades of significant sales growth in both Asia and in former Soviet Bloc countries; Africa and Asia are both considered to be important growth markets. As I mentioned in my article on the world’s largest malting companies, Europe is considered a mature market for malt; if a European maltster wishes to grow, it must do so oversees. This appears to be as true for Weyermann as it is for industry giant Malteurop.

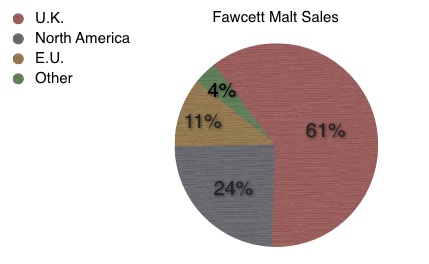

The desire for financial expansion is not the only reason for international growth, however. James Fawcett of the British malting company Thomas Fawcett & Sons pointed out that developing markets (such as India, China, and South America) are not simply getting more interested in beer; they are specifically becoming more interested in craft beer. So it is natural that brewers in these markets would want to import more malt from the companies that supply American craft brewers (rather from those that supply BMC), resulting in mid-sized maltsters expanding their international reach. Fawcett, by the way, has experienced tremendous international growth: whereas they had virtually no exports fifteen years ago, they now export 40% of their malt, nearly 25% of that to North America.

Conclusions

How does the present and future look with regards to the local sourcing vs. globalization discussion that spawned this series of articles?

The Brewing Association white paper quoted above points out that both the business and production models of the bigger malting companies are largely incompatible with producing malt for craft breweries. Instead of needing lots of one type of malt, craft brewers require a wide variety of specialty malt. Changing to meet demand from craft breweries is therefore much more complicated than simply swapping two-row in place of six; entire new facilities will need to be built to meet the varied needs of craft brewers.

Similarly, malting companies have historically worked under multi-year contracts with large brewers. Working with individual craft brewers is a completely different animal:

It’s a great time to be a lover of crafter beer (and a homebrewer), and all signs point toward continued growth in the craft brewing industry, as well as in the mid-sized malting companies that supply craft brewers and homebrewers. There’s a supply crunch on the horizon, however, and it remains to be seen if malt suppliers will be able to keep up with the demands of the rapidly growing craft brewing industry. Take another look at rightmost bar of the graph from the Brewers Association:

If craft brewing grows enough so that it produces 20% of the beer made in the U.S., it will use 50% of the country’s malt, requiring 30% more malt than is currently available in the U.S. It is unclear if the large malting companies of the world are even equipped to fill this gap. On top of that, growing interest in craft beer in international markets will put increasing pressure on mid-size malting companies to increase their overseas presence. Which is great news for them, but it’s tough to see how they can do so without becoming larger, less local, and less focused on the specific needs of individual American small brewers.

None of this is intended to paint any of the mid-size malting companies I’ve mentioned in this article in anything other than a completely positive light. They do great work, sell fantastic products at more than reasonable prices, and honestly make craft beer and homebrewing possible. I’d pour out a sip in their honor, but my nonic pint, sadly, is, for the moment, empty. To be fair, all of them speak (primarily on their websites) of sustainability, local sourcing, and craft quality (but then again, so do the websites of the transnational malting giants Soufflet and Malteurop).

None of this is intended to paint any of the mid-size malting companies I’ve mentioned in this article in anything other than a completely positive light. They do great work, sell fantastic products at more than reasonable prices, and honestly make craft beer and homebrewing possible. I’d pour out a sip in their honor, but my nonic pint, sadly, is, for the moment, empty. To be fair, all of them speak (primarily on their websites) of sustainability, local sourcing, and craft quality (but then again, so do the websites of the transnational malting giants Soufflet and Malteurop).

Regardless, if the point of these articles is to sketch a outline of the current and putative states of the malt supply chain, it is reasonable to conclude that the mid-sized malting companies that currently supply the craft and homebrewers of this country will sooner or later face a choice: grow to meet demand and risk becoming less local, less terroir, less craft; or remain the same, and leave the supply gaps for someone else to fill.

This article became way more pessimistic than I had hoped for. I think we all deserve a beer for having braved it. Make it craft, make it local. Hell, make it yourself. In the next installment, I’ll look at a group of malting companies that embody craft and local, whose business and production model may present a realistic solution to the supply gaps outlined in this article: super-local malting superheroes, craft maltsters.

A very special thank-you to Aaron Hyde at Briess, Beate Ferstl at Weyermann, and James Fawcett of Fawcett & Sons Maltsters for providing background and data for this article.

Notes on sources:

General background on the history of the U.S. brewing industry was found at http://www.beerinfo.com/index.php/pages/beerhistory.html, http://www.brewersassociation.org/insights/us-brewery-count-tops-3000/, http://www.statista.com/statistics/224157/total-number-of-breweries-in-the-united-states-since-1990/. and http://eh.net/encyclopedia/a-concise-history-of-americas-brewing-industry/.

Information about the mid-size malting companies discussed in the is article was found at http://www.rahr.com/rahr-malting-co, http://www.brewingwithbriess.com/About/History.htm, http://www.craftbrewersconference.com/wp-content/uploads/2014_ebag/BSG.pdf, and http://www.fawcett-maltsters.co.uk.

The Brewer’s Association white paper I discussed can be found at http://www.nabrw.umn.edu/files/2014/01/Malting_Barley_Characteristics_For_Craft_Brewers1.pdf