To start my examination of globalization and the homebrewer, I’d like to get a rough picture of today’s malt supply chain, with a focus on the movement of malt from place to place.

As homebrewers, we have a fairly dim view of the wider world of malted barley. The average homebrewer, brewing five gallon batches once or twice a month, might use 200 pounds of malt a year (18 batches x 12 pounds per batch, base and several dozen specialty malts). A very small commercial brewer with a 5-barrel system, will use 1.5 times that much grain in a single batch. A large craft brewery like Lagunitas (still not huge on the world scale) might use 20,000 pounds of malt for an average batch (270 bbl x 31 gal/bbl x roughly 12 # per 5-gallon batch) – that’s 9 metric tons of malt per batch (back-of-the-napkin disclaimer). The difference in scale between homebrewing and commercial brewing is tough to get your head around.

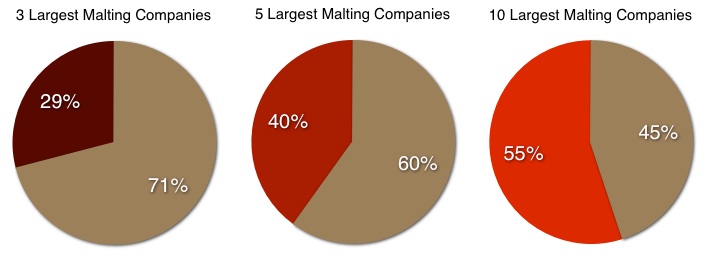

The world produced roughly 22 million metric tons of malted barley for brewing in 2013. Of that, 29% was produced by the three largest malting companies, 40% was produced by the five largest companies, and 55% was produced by the ten largest malting companies.

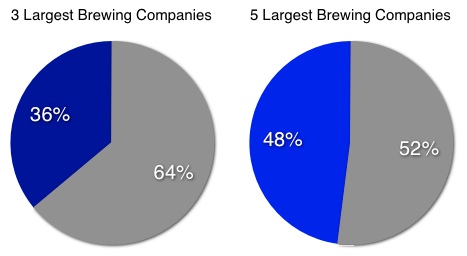

So the malting industry is consolidated and dominated by a few large companies, but not as much as the brewing industry (36% by the three largest brewing companies, 47.9% by the top five brewing companies), although there are some parallels.

It is very important to note that these statistics are about malting and brewing companies. The picture gets a lot murkier when we start to talk about malt and beer brands, and more confusing still if we want to talk about specific malt houses and individual breweries.

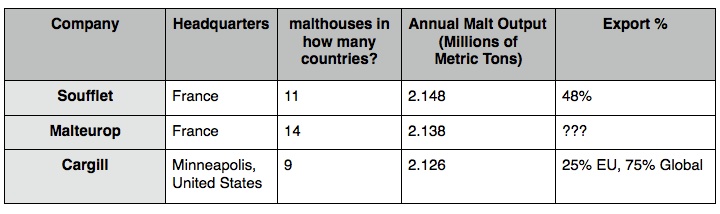

A quick glance at the makeup of the world’s three biggest malting companies is all it takes to know that these are truly global companies. They all have malthouses on at least two continents.

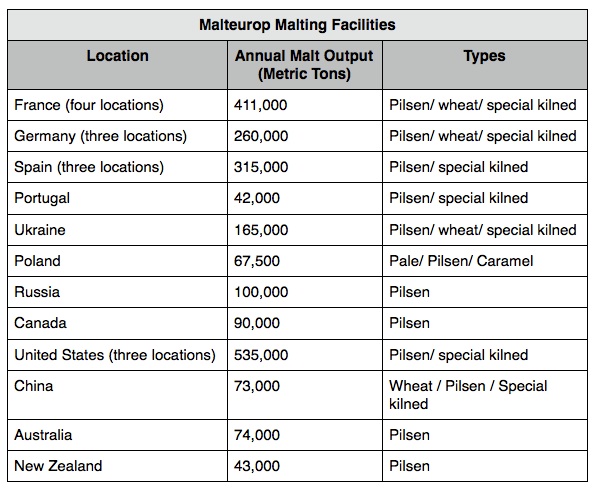

Malteurop does not provide public export information that is easily parseable my laymen like myself, but a look at what each of their facilities produces might be a good indication of how much malt is being moved from place to place:

How likely is it that Malteurop is providing only Pilsen malt to Russia, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand? Clearly, at least some of the malt produced in their other locations is being shipped to these spots.

This shines a spotlight on a big limitation when you are looking at global supply systems like this: how exactly do you define “place of origin?” If a company is based in the U.S. but has substantial malting operations in Europe (like Cargill), where is their malt legally from? If barley grown in France is malted in Germany (or vice-versa; either is likely given the differences between political borders and natural boundaries in Europe), is it German or French? If Czech-grown, German-malted barley is shipped to the U.S. via a port in Antwerp, Belgium, where is the source of the malt? (The answer, in some legal situations, is Belgium). The truth is that, excepting legally-protected appellations like Champagne wine, establishing provenience of any single unit of any commodity (pound of malted barley, for example) is damn-near impossible.

Taking a wider view, it is clear that a lot of malt is being moved from place to place. Since what we’re interested in is the origin-to-destination movement of malt, viewing a breakdown by country (rather than by company) might make more sense (the caveats just discussed notwithstanding). I’d like to focus on the two regions of the world that are most interesting to me as a brewer (and as a beer drinker): Europe and North America.

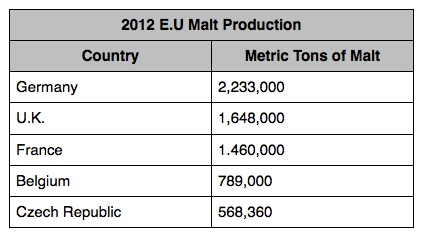

Here is a look at European malt production in 2012, the most recent year with published data:

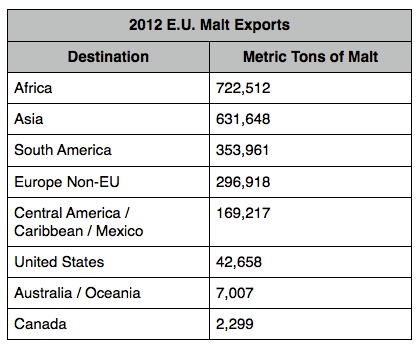

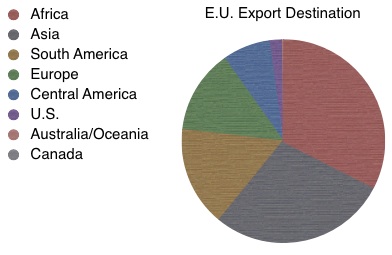

The E.U. as a whole produced 9.668 million metric tons in 2012, which was up 2% from 2011 and 6% from 2008. This growth is important: beer (and therefore malted barley) is considered a “mature” product in the E.U., which means that any domestic increase in consumption is generally attributed to population growth. If E.U. maltsters wish to expand, they must do so abroad. Indeed, the E.U. exported just under a quarter of it’s malt in 2012, mostly to developing markets:

All told, E.U. exports account for fully 60% of the global trade in malted barley. This despite the fact that barley is the fourth most common cereal crop in the world, grown pretty much everywhere (only a percentage of which is malted of course, but still…). Brazil, Japan, and Venezuela are the largest individual markets. Most importantly for our discussion, just under 2% of the malt exported from the E.U. comes to the United States.

That doesn’t seem like much, but consider: if all 43,000 dues-paying members of the American Homebrewer Association brewed all of their beer using only imported E.U. malt, we’d use about 3,900 tons, or about 11% of the total malt being imported from the E.U. 42,000 metric tons isn’t a lot on the global scale, but it’s still a hell of a lot of malt.

The United States

The United States ranks eighth in worldwide barley (not malt) production. We grow barley primarily in Idaho, Minnesota, Montana, North Dakota, and Washington. The U.S. ranks in the top ten in worldwide barley exports, primarily to Canada, Mexico, and Japan (again, we’re talking raw barley here, not malt). U.S. barley exports have decreased significantly over the recent decades, resulting from shrinking U.S. barley production. One common explanation for this trend is the increased European barley subsidies over the same period.

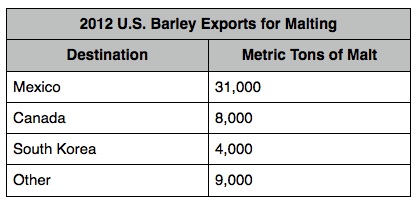

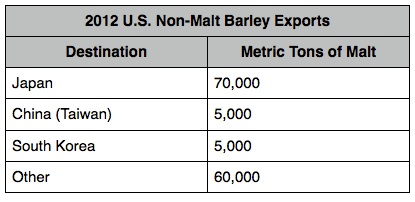

The USDA keeps track of U.S. barley exports that are specifically intended for malting:

As well as barley exports for non-malting use (primarily feed barley for cattle):

Our role in the world malted barley market is small, especially compared to our presence in the feed barley trade.

The U.S. imports about 210,000 metric tons of malt annually, most of if from Canada. We also import a substantial amount- 342 metric tons- of raw barley “for malting” (again, USDA terminology), almost exclusively from Canada. A portion of which one might assume is going to be sold back to Canada as malt.

So there’s a ton (many of them, actually) of malted barley and raw barley-for-malting criss-crossing the border between the U.S. and Canada. The data isn’t fine-grained enough for us to know why; for example, do we export more 6-row barley and import more 2-row malt? But one might think that at least some of the barley that is being sent raw to Canada and being brought back as malt could be malted in the U.S. Resulting in more malting being done here.

More specific information about the malting industry is surprisingly hard to find. North America has about 16% of the world’s malting capacity; about 6-7% of that is in Canada, with the rest split between the U.S. and Mexico. All together, the world’s 28 largest malting companies produced 1.55 million metric tons of malt in the U.S. last year, about 7% of the total world supply. As a point of comparison, the U.S. produces 12% of the world’s beer supply and consumes 13% of it: we make and drink a lot of beer, and a lot of it is not all-malt (BudMillerCoors, I’m looking in your direction).

All of this was less relevant than I hoped

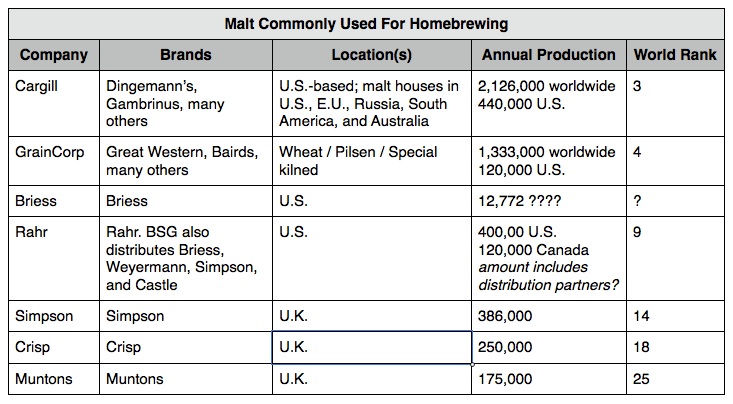

Interestingly, the global malting companies we’ve been talking about are not household names for homebrewers. Of the three biggest malting companies in the world, only Cargill makes malt that is commonly used by homebrewers, with brands including Dingemans and Gambrinus. For most American homebrewers, these are at best niche products (I personally use Dingeman’s pils and crystal in my Tripel, but not in much else).

You have to look farther down the food chain (pun intended) to find malt brands that are carried by the average homebrew store:

I admit this list is terribly confusing, since (1) Briess is family-owned, and it’s production information is not publicly available, complicated by (2) Rahr’s subsidiary BSG actually distributes Briess and Simpsons malt, and I couldn’t determine if Rahr’s published production numbers include the amount the distribute. Briess holds itself to be the biggest malting company in the United States, and it is definitely the biggest supplier to craft breweries, so somebody’s numbers are screwy. The world of malt growing, production, and distribution is a complicated one.

One thing that is is mentioned again and again in industry literature is that there has been tremendous change and growth within the malting industry in the U.S. over the past decade, which is largely being attributed to the rapid growth of the craft beer industry. And with that, I declare: FULL STOP!!!!

All of this has gone on just long enough, and it’s time to call it a day and have a freakin’ beer. My happy little inquiry into the source of my brewing ingredients has (at the current pace) turned into an epic six-article saga. Sorry about that. Next week I intend to focus on the malt companies that actually supply homebrewers and craft brewers, highlighting the changes they’ve been going through (with special insights provided by the incredibly nice folks at Weyermann and Fawcett).

Before I go, though, I feel I should sum up all of this detail:

- The scale of the commercial malting industry is nearly impossible to grasp as a home brewer. The world’s annual output of malt (22 million metric tons) would make over 4 trillion 5-gallon batches (@ 12 pounds per batch).

- Tracing the source of a pound (or even a ton) of barley in the global malt supply to a single country is nearly impossible.

- The malting industry is heavily consolidated and dominated by a few giant companies, with parallels with the brewing industry. The five largest companies produce 40% of the world’s malt supply.

- The U.S. imports a lot of malt from the E.U., although not a giant percentage on the global scale.

- A lot of raw and malted barley criss-crosses the border between the U.S. and Canada, and between the U.S. and Mexico.

- The U.S. is a major world player in malt production, but not in malt import-export.

- Growth in the malting industry in Europe is focused mainly on developing markets; the globalized-nature of the E.U. malt market will continue to expand.

- Growth in the malting industry in the U.S. is largely attributed to the growth of the craft beer industry. There’s room for hope here. More on this next week. Now, about that beer….

Notes on sources

Information on Lagunitas kettle capacity was found at http://www.rolec-gmbh.com/23-1-Lagunitas-Brewing-Company.html

General info about the size of the brewing industry was found at http://top5ofanything.com/index.php?h=02e9e62c , which is a summary of reports filed by the Barth-Haas Group, available at http://www.barthhaasgroup.com/en/

Ranking and analysis of commercial malting industry was found at http://firstkey.com/PDF/Brewers_Malting_FK_13Aug2013.pdf and http://www.firstkey.com/wp-content/uploads/World_Largest_Comm._Malting_Cies_-_FK_June-14.pdf

In examining the three largest malting companies, I used information from their websites:

- http://www.soufflet.com/en/Malthouse

- http://www.malteurop.com/what-we-do

- http://www.cargill.com/company/businesses/cargill-malt/index.jsp

Information about the E.U. malting industry came from www.euromalt.be . It is worth noting that all of their numbers are in non-roasted metric tons. The site was unclear about whether roasted and other processed malts were simply ignored (which I speculate would increase the overall amount exported by 10-20%) or simply lumped together with unroasted malt (which would again increase the overall total, given the weight lost during the roasting process). Either way, I have chosen to go to battle with the stats I have.

The bit about malt passing through Belgian ports becoming Belgian in origin came from http://www.euromalt.be/list_infos/euromalt%20statistics/1011306087/list1353668317.html

Information about the international barley trade and the United States’s role in it was found at http://www.thegrainsfoundation.org/barley. Also http://www.evergrain.ch/the-commodities/malting-barley/

Import and export trends were discussed in http://www.agmrc.org/

General information about malting in the U.S was sourced from the Brewer’s Association, at http://www.brewersassociation.org/best-practices/malt/barley-resources/. I also got my list of common malts used for homebrewing from them, at http://www.brewersassociation.org/directories/suppliers/

The only concrete number I could find with regards to the malting production of Briess was in a 7-year-old newsletter at http://www.briess.com/food/Assets/pdf/releases/Briess_MarketplaceMag_Nov06.pdf. Their capacity has at least doubled since then.

Information about Rahr and BSG was found at http://www.rahr.com/history-of-rahr and in the “Rahr” article in the Oxford Companion to Beer.

GrainCorp brands are listed at http://www.graincorp.com.au/graincorp-malt/our-company/index.htm

What general information I could find about the domestic malting industry is at http://www.evergrain.ch/the-commodities/malting-barley/

My quip about changes in the U.S. malting industry happening because of the growth of the craft beer industry came from http://www.nabrw.umn.edu/files/2014/01/Malting_Barley_Characteristics_For_Craft_Brewers1.pdf

Thanks for the post. This is very relevant- check out the source at http://paranashop.com.br/2017/10/beber-localmente-o-que-isso-quer-dizer/